Faisal Mosque designed by Vedat Delokay is an iconic architectural landmark that requires no introduction. Given its contradictory form in the canonized context of mosque architecture in South Asia, the complex has more to offer than just the quintessential definition of an area to offer prayer. In this article, 3rd year students of History and Theory of Architecture at SADA have investigated the ideology behind a religious building and how its architectural aesthetic is influenced by the contemporary and historical socio-cultural norms of its modern-day metropolitan context.

The Recent Placement of The Faisal Mosque Amongst the Historical Context of South Asia

“Architecture tells us not what men were at any period of history, but what they dreamed” – Joseph Hudnit

Delokay’s competition winning design for a mosque in Islamabad is an eight-faceted triangular pyramidal concrete shell structure under a gabled roof with apparent influence from Greek gabled architecture. Despite the construction of the mosque being completed recently, it is already considered to be the second-largest mosque in the world and the largest in South Asia. The construction expresses the dreams of modernity and development that Pakistan holds for its capital city how the same modern and unique style has been followed throughout the metropolitan city itself.

However, it is to be mentioned that Pakistan, as well as all South Asia, has a deeply rich historical heritage when it comes to Islamic Architecture. Muslims have been in South Asia since before the 8th century. During this time, Islamic Architecture took influences from local cultures, vernacular materials and built many areas of worship, gardens, palaces, and mosques. This Indo-Islamic Architecture illuminated all over the sub-continent and established a language of ornamentation, calligraphy, and construction that hold significance and meaning over Islam and its culture in South Asia to this date. Yet none of this heritage can be seen in the form, ornamentation, or materials of the Faisal Mosque. Mughal Architecture is known for using local red sandstone, and brick to make their iconic structures. Faisal Mosque’s concrete shell has been cladded with white gesso’s marble from Turkey, while the interior is adorned with a Turkish chandelier. A little Pakistani art can be seen in the design of the mihrab and minbar, but even those are not recesses and niches, but modern sculptural elements. It is worth noting the presence of the painting done by our very own famous local artist, Sadeqain, within the main prayer hall attempts to pay homage to all local art. However, one painting is not enough and if anything, it ends up feeling like a consolation prize instead. Although collaboration was common even in historic and Mughal Architecture, with material coming in from all over the world, this ends up feeling less like a collaboration because Pakistan’s role in the project’s design feels secondary and its heritage remains completely ignored.

The King Faisal Mosque’s approach is understandable under the present context and its aspirations; however, it is incomprehensible that very little has been done to represent or pay homage to a beloved and celebrated architectural heritage in a project that will undoubtedly reach its potential as a monument of Islamic Architecture all around the world.

Faisal Mosque and the evolution in its primary function: a symbol, a social space, or a place for prayer?

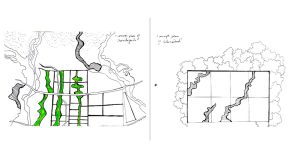

A mosque, historically, is not a structure reserved purely for religious purposes and the fulfillment of religious obligations; it is in its pure essence a space for dawah (invitation and education of religion), which establishes its status as a social space. The recent inauguration of the Faisal Mosque makes us imagine the potential of the mosque as a social space in the context of Islamabad regarding the growth of the city. The newly established city lacked an identity beyond its status as a capital; and as most urban nodes centers do, did not have symbolic representation until Delokay brought the great architectural establishment to life. The mosque with its monumentality in scale, form, and strategically deliberate location, holds the potential to become an inherent part of its name. What contributes to this, is the mosque’s incredible visibility, and the axis that Faisal Avenue forms, bypassing the city towards the Margalla Hills. However, beyond just utilitarian notions, it appears to be a space that will be chosen by the people of Islamabad as their identity.

The layout of the mosque offers a segregation of these overlapping identities by enclosing the religious sanctuary in a closed plan, while the open floor plan has potential to embody the social space. We see it as a space for children and women, men, and elderly, with the open courtyard not having physical barriers, facilitating the pre-existing familial culture of the local context. We see it as an educational site, and a case study for engineers and architects, with the girders, cross beams, and hyperbolic paraboloids accentuating the possibility of innovation in structure. We see it as a space for poverty to disseminate with the hope of generosity in a religious space alive upon tradition. We also see the establishment as a cause for property sales, rates, and values to fluctuate, and the mosque embodying its roles as an urban node, a junction for vehicular traffic, and an economic landmark overwhelm the primary function: a place for prayer.

Faisal Mosque: A Deviation from Islamic Architecture or A Contemporary Take on It?

With its monumentality and strategic location within the capital city, Faisal Mosque has proved itself to be a sight hard to miss. While that may be true, the ongoing debate about the deviation of Faisal Mosque from traditional Islamic architecture has been just as difficult to ignore. After a lack of what many consider ‘Islamic Architecture’, observed inside the mosque, most wonder whether hiring a Turkish architect instead of a local one was the best decision.

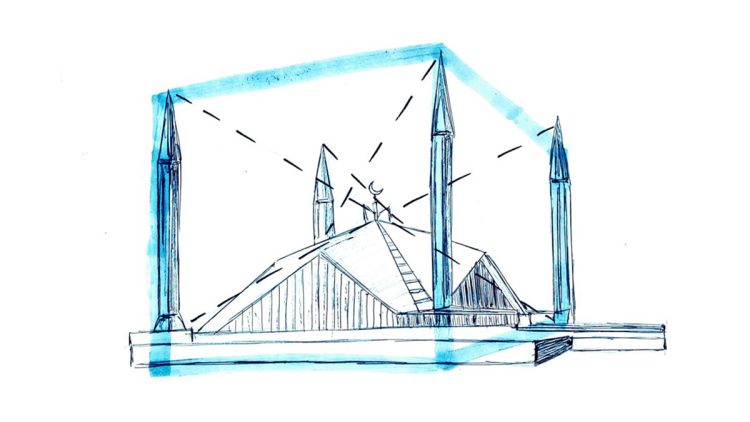

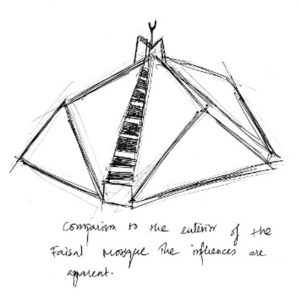

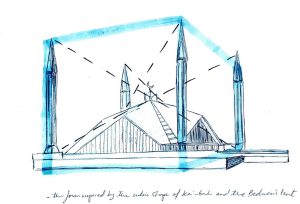

Those who argue against this decision purely based on its nonconformity from Islamic Architecture may stand corrected once they realize that while the architectural translation is different from the local existing examples, every element has been strongly inspired by Islamic Architecture. The same tent shape of the mosque that classifies it as a modern, contemporary establishment is the same form that has been derived from none other than the Holy Kabbah itself. The four minarets pay homage to the Kaabah by connecting with one another through a cubic shape like that of its form, while the tent-like form is derived from a desert Bedouin’s tent.

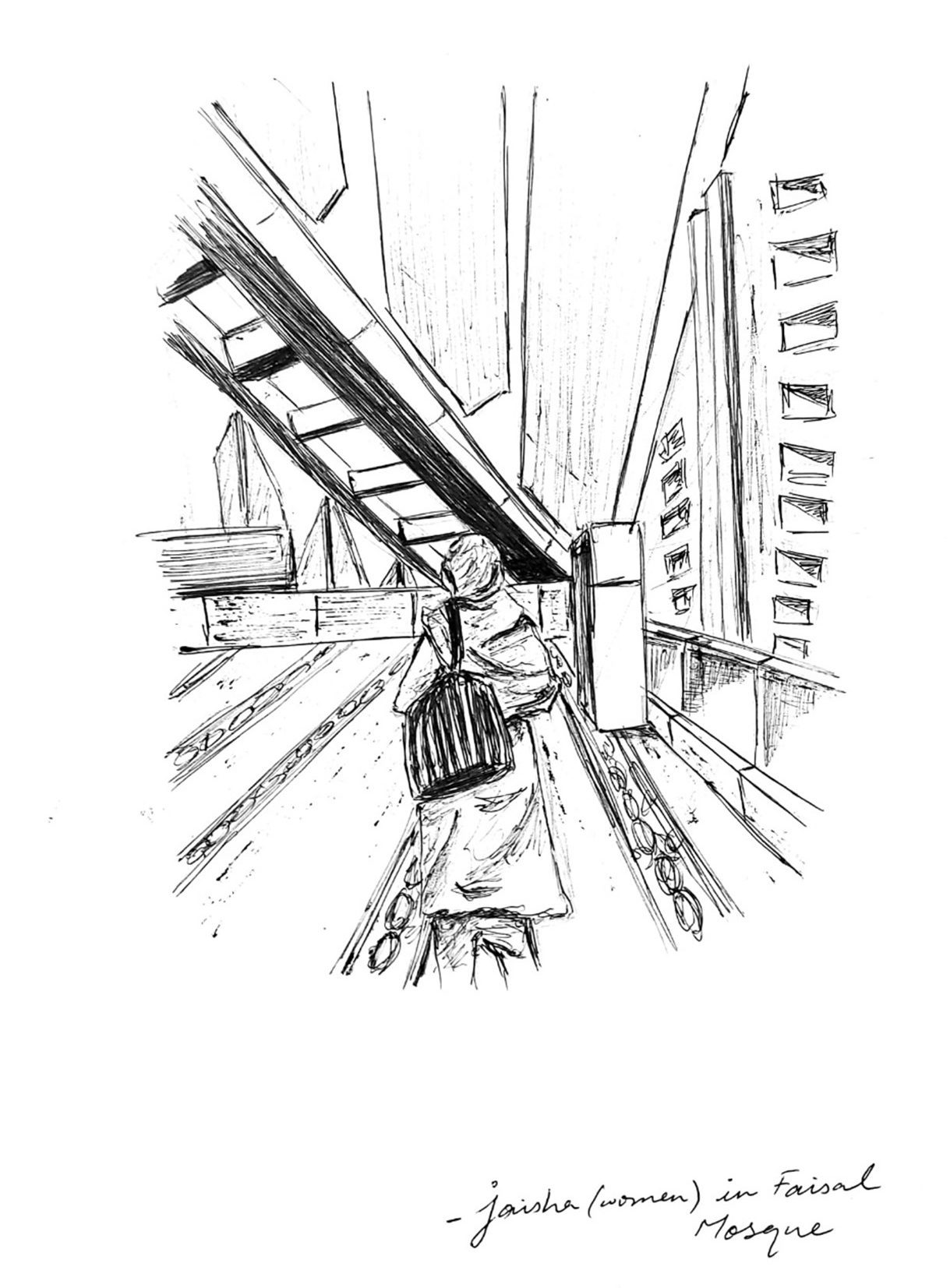

Not only that, but the more one goes inside – the more one starts seeing similarities to Islamic architecture through the tile mosaics adorning the ablution areas, the lattice work on the women’s gallery, the familiar geometrical and Kufic calligraphy patterns on the walls, the reflected mirror mosaics, the presence of Surah-e-Rehman in front of the mihrab and the arches shown through porticos in the courtyard. Hence, it can be argued that it is not that Faisal Mosque did not follow traditional Islamic architecture but, instead that it decided to take those features and translate them in a more abstract manner by choosing a somewhat unique and unusual presentation of design. The variety of shapes and architectural elements are all inspired and taken by Islamic architecture, it is only the composition and arrangement of those elements that does not follow any traditional design formation.

Faisal Mosque as a Political Assertion

When Ayub Khan proclaimed the promise of a Grand Mosque in 1966, the motivation for such a suggestion by King Faisal could easily find commonality with the hiring of Doxiadus as the primary planner for the capital city hosting the mosque. The 1960s was a time when Pakistan desperately sought international acceptance and the superimposed plans of Islamabad are a manifestation of the uncompromising endorsement of modernity that prevailed as a result.

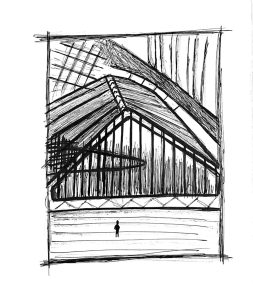

Beyond the architect’s identity, however, the advocacy of strictly orderly and linear articulation in the design of the building and the architectural language, unprecedented in South Asia is observed. A remarkable level of innovation in technology flaunts the intelligence of the newly formed nation which is evident through the replacement of the conventional dome quintessential to Islamic architecture with triangular isosceles slabs, supported not on walls but on girders that bear the load of cross beams and hinge beams where vaults with harsh contours compliment the exterior language. These folded slabs are visible from the apex of the prayer hall, while ladders culminate at the peak. A rationale for abandoning traditional elements such as the dome, the traditional minaret, and inherited elements from subcontinental architecture known for being heavily drenched in symbolic and historical relevance is to express a dissociation with pre-partition mindsets. It is to express a conformity to the globally relevant stylistic movements of our time such as geometric art, post modernism and early traces of deconstructivist architecture. This government, as the new elite of a post-colonial country, views itself as the custodian of aesthetic values that justify monumentality as the most effective way of communicating their legibility, no matter how ill-tuned it may be from the needs of this new society.

Monumentality: Would This Design Still Be Considered Successful had it been executed on a Smaller Scale?

The inauguration of the Faisal Mosque in Islamabad has created several opinions among the residents of the capital city. It is a structure that could be regarded as an impressive example of modernist architecture. In future, it will not only act as a landmark but speculations about calling it the national mosque of Pakistan are also underway. Additionally, it could also become the graphical representation of the city of Islamabad. Its grand size and impressive scale are integral to its impact and significance, and the building has become an iconic symbol in the vicinity. However, it is worth considering whether the Faisal Mosque would still be considered a success if it were not for its monumentality.

While the triangular windows and crescent fenestration design that adorn the exterior of the mosque do contribute to its visual appeal, it is the overall size and scale of the building that really makes it stand out. Without the massive prayer hall, lit up with a gold-plated chandelier, the expansive open area to walk around, and the huge chunk of green areas, Faisal Mosque would likely just be another modernist building, rather than the iconic and majestic structure that is being celebrated right now.

One could only imagine this mosque being built at the scale of a local mosque in any other neighborhood in Islamabad. It is very likely that the reception would not have been this welcoming for a structure that could be characterized as an invasion of the existing architectural context. However, since the stakes were so high and the scale so imposing, the alien structure was forced to be celebrated as something that held more political value than it did cultural or social.

Additionally, the functionality and practicality of the Faisal Mosque are greatly enhanced by its size. The ample space and layout of the building allow it to accommodate large numbers of worshippers and facilitate the flow of people during prayer times. These aspects of the design would likely be compromised if the building was built on a smaller scale. More importantly, the users would not be so indifferent to the design flaws within the structure if it were not for the pre-conceived mindset communicated through its grandeur.

In conclusion, while the design elements and functionality of the Faisal Mosque are certainly important, it is the monumentality of the building that truly sets it apart and makes it a success. Without its scale, the Faisal Mosque would not be making headlines!

This article has also been co-authored by 3rd-year Students of Bachelor’s in Architecture namely Mohammad Umar, Rija Zaki, Duha Mohsin, and Jaisha Mubashir.

Bibliography

Dalokay, C. o. (n.d.). Neelum Naz. From https://bit.ly/3iI6NB0.

Deaschul, M. (2015). Islamabad and the Politics of International Development . Cambridge University Press.

Hudnit, J. (1949). Architecture and the Spirit of Man.

Jamil, R. (n.d.). Conserving the Religious and Traditional Values of Muslims with a Dome-less Mosque Architecture: A Case Study of Shah Faisal Mosque, Islamabad. From https://bit.ly/3GVUCZs.

Mujahid, A. M. (n.d.). Challenges of women space in Masjids. From https://bit.ly/3J0datZ.

Nasim, S. (2008). Tile Mosaic Decoration and Colour Philosophy in Ablution Area of the Faisal Mosque. From https://bit.ly/3ZHh1lD.

Nasim, S. (2020). Decorative Elements of the Faisal Mosque Islamabad. Thesis. From https://bit.ly/3QOTE5F.

Saleem, M. H. (2022). Historical Architecture of South Asia: The Rise of Indo-Islamic Construction. From Artshelp: https://bit.ly/3XBsHEL.

The author is a Lecturer in the Department of Architecture in School of Art, Design, and Architecture (SADA) at the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST). She can be reached at sidra.khokhar@sada.nust.edu.pk.

![]()