Herman Daly, the renowned ecological economist, in his book, The Steady-State Economics (1977), exposes the fallacy inherent in the concept of unlimited growth which is based on the refusal or failure to realize that the environment, which encloses all socioeconomic activity since  the latter takes place within the confines of the former, is a limited and finite resource. This insight lies at the heart of the concept and practice of sustainable development which is based on the idea of responsible growth bottomed on cultivating a careful and respectful relationship with the environment.

the latter takes place within the confines of the former, is a limited and finite resource. This insight lies at the heart of the concept and practice of sustainable development which is based on the idea of responsible growth bottomed on cultivating a careful and respectful relationship with the environment.

Unfortunately, this insight has failed to substantially influence the real-world practice of global politics. This is because the myth of unlimited growth, in which the environment does not matter, goes hand in glove with power politics. The mad race for increasing one’s own relative power at the expense of competitors and adversaries has historically distracted states, developed and developing alike, from pursuing sustainable development single-handedly.

While advanced countries have managed to develop at the same time that they have led the practice of power politics, developing countries have struggled with the simultaneous demands of security and development. There may also not be an easy unanimous answer to the question whether the development of the advanced countries is sustainable if all other countries, big and small, were to develop in the like manner at the same rate using the same strategies like the ones adopted by advanced countries in their race to the top.

While the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development has been accepted by the world community, this global consensus has not translated into an all-round tangible financial commitment and development practice on the part of major developed and developing countries to realize the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A cursory glance at the major world regions, especially Eurasia, will show that power politics continue to frustrate the building of such a consensus.

The 2030 Agenda offers a rare opportunity for all countries to collectively transcend the narrow and  destructive horizon of zero-sum politics. The world will make a big stride toward peace and stability if the top 17 economies of the world were to collectively agree that each of them would become the global champion of at least one SDG and devote own resources toward the global achievement of that SDG as well as lead the cause of building multilateral partnerships for organizing multiple resources, including financial and human resources, towards the realization of the SDG that it championed. These global SDG champions could also work with important regional countries to fast-track the realization of all the 169 targets of the 17 SDGs. Alternatively, the top 20 economies of the world could collectively spearhead the phased achievement of sustainable development in Africa, Asia, and Latin America till 2030 creating dynamic multidimensional state and non-state partnerships for this purpose.

destructive horizon of zero-sum politics. The world will make a big stride toward peace and stability if the top 17 economies of the world were to collectively agree that each of them would become the global champion of at least one SDG and devote own resources toward the global achievement of that SDG as well as lead the cause of building multilateral partnerships for organizing multiple resources, including financial and human resources, towards the realization of the SDG that it championed. These global SDG champions could also work with important regional countries to fast-track the realization of all the 169 targets of the 17 SDGs. Alternatively, the top 20 economies of the world could collectively spearhead the phased achievement of sustainable development in Africa, Asia, and Latin America till 2030 creating dynamic multidimensional state and non-state partnerships for this purpose.

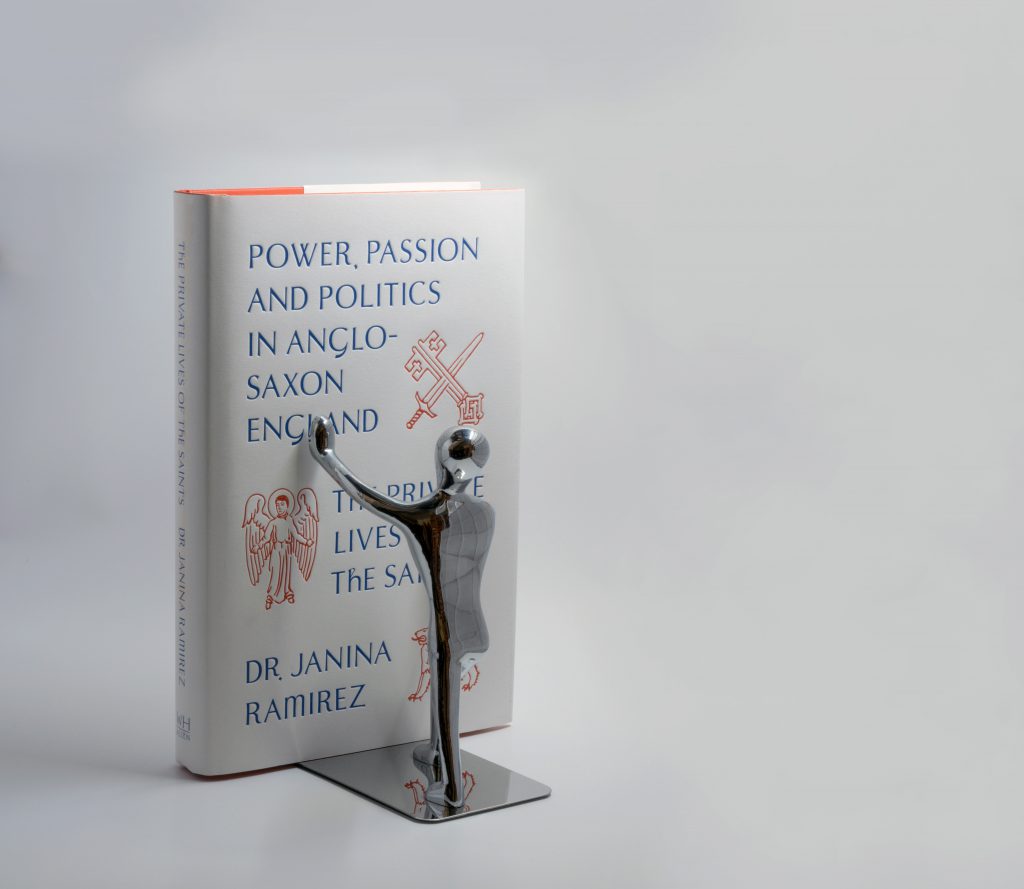

There is also a need to rethink the conceptual category of great power. We need to move beyond the martial and war-centric definition of great powers. A great power should not be defined, as John Mearsheimer, the famous expert on international relations, has done in his book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (2001), as a state that has “sufficient military assets to put up a serious fight in an all-out conventional war against the most powerful state in the world” but as a state that has demonstrated and continues to display sustained and successful contribution to the achievement of SDGs.

As long as mankind does not consciously and decisively abandon power politics, sustainable development on a global scale will not be realized comprehensively. In order to achieve sustainable development in its three dimensions, namely, social, economic, and environmental, as the 2030 Agenda envisions, the political domain needs to be civilized further based upon the realization that there cannot be any geopolitical fix to the problems of development.

The author heads research and analysis at the NUST Institute of Policy Studies (NIPS) and can be reached at ali.shah@nust.edu.pk