Every year since 1999, the UN celebrates February 21 as the International Mother Language Day. This year, the Day was celebrated with the theme, ‘Multilingual education – a necessity to transform education” to highlight the importance of indigenous people’s education and languages.

Mother-tongue, alternatively known as native language, first language, or L1, usually refers to the language(s) acquired during early childhood through interaction with surrounding adults. While this definition may not be the only explanation of the concept, every individual does have an understanding of their respective native tongue. In many parts of urban Pakistan, during the last two decades or so, children have grown up acquiring their first language(s) with a predominant involvement of English language not only through their interaction of family members, neighbours, school teachers, and friends, but also through their consumption of educational and entertainment content in English language. As a medium of instruction, English is highly valued in our country and concerted efforts are made to improve fluency and proficiency in English language across all segments of the society. On the face of it, there is no harm in promoting and improving proficiency in a lingua franca for obvious reasons, however, elevating one language while ignoring a host of mother-tongues can have far reaching effects on a single, as well as the global community, as identified by the UN in their Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

SDG 4 focuses on education and aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. With over 7000 living known languages, almost 2.3 billion people across the world lack access to education in languages they are familiar with. The idea, therefore, is simple: providing education that begins in languages that the learner is fluent in, before introducing other languages gradually. This is in pursuit of the vision of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) of inclusive, equitable and quality education for all, which directly addresses mother tongue-based multilingual education (MTB-MLE).

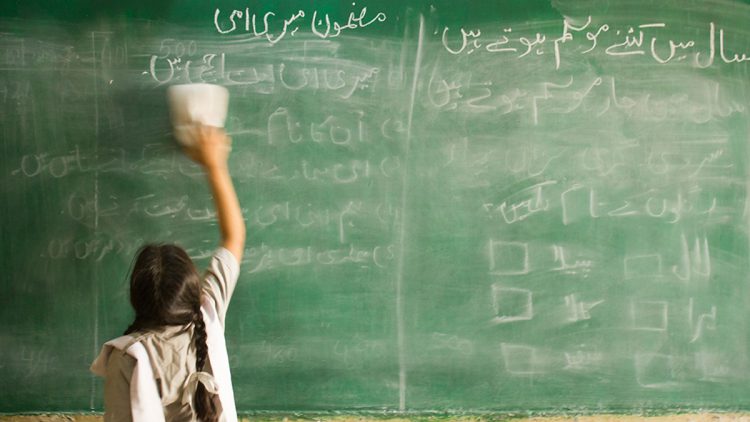

Internationally, mother tongue-based multilingual education (MTB-MLE) has been recognized as the most effective learning model for ensuring that students from diverse linguistic backgrounds become multilingual learners, remain in school, and actually learn. Here, it will be a gross misunderstanding to assume that MTB-MLE discourages from using other languages (national or international) during the process of classroom instruction. It rather follows a simple yet logical method. The teaching starts in the learner’ mother language with other languages also used side by side. At the outset, the first language is the dominant medium of instruction and learners develop a strong foundation in their mother language before adding additional languages over time. The idea should not surprise us; after all many children grow up in environments with more than one language spoken around them. Pakistan is certainly one such case!

In Pakistan, efforts have been made to use MTB-MLE as a viable teaching method, albeit at a limited scale. The most successful efforts have been largely initiated by non-profit organizations. Among the provinces, who have the autonomy to select the language for instruction at school level since 2009, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh have introduced books in local languages; however, other provinces still have to follow suit. More recently, local communities in parts of Sindh have established their own MTB-MLE schools, though still unrecognized by the provincial government (Rahman, 2019).

In Pakistan, the fundamental components of MTB-MLE with SDG 4’s targets can benefit both individual learners as well as the society where not only the regional languages and dialects avoid endangerment but also help young students learn core concepts efficiently. The benefits of choosing this system do not end with the students in the classroom. Parents participate more in their children’s learning by supporting teachers and taking part in other school activities. Marginalized communities are able to maintain their own linguistic and cultural identities while interacting with dominant wider cultures. Overall, improved academic results, lower dropout rates, and better proficiency in both the learner’s first, official and international languages are some more benefits. In the long run, real learning and better language skills means more access to job opportunities and more peaceful communities.

Keeping the above discussion in view, MTB-MLE is not only important to the global education agenda, it is also an important part of sustainable development aimed at ending poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring prosperity for local communities as well. Since setting curriculums and revisiting the education policies is a continuous process, it can be hoped that the Pakistan would positively consider the practical MTB-MLE model for its country-wide implementation to take an important step towards meeting SDG 4.

Reference:

Rahman, T (2019) ‘Mother Tongue Education Policy in Pakistan’, in: Patrick AK, Anthony AJ and Coat, L (eds) The Routledge International Handbook of Language Education Policy in Asia. London: Routledge, pp. 364-381.

The author is Head of Department of Mass Communication, at School of Social Sciences and Humanities (S3H), National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST). She can be reached at samavia@s3h.nust.edu.pk.

![]()